Rediscovering the Dignity of Work

How Ronald Reagan’s Favorite Novel Can Teach Us to Work — and Live — with Purpose

The purpose of life is not to be happy. It is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to have it made some difference that you have lived and lived well.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

In the Reagan (2024) film, an ambitious young Russian politician meets with a grizzled KGB veteran who had spent decades surveilling Reagan, from his days as an actor through his presidency. The young politician poses one crucial question: Why did the Soviet Union lose the Cold War? The answer lies not in military strategy or economic policy, but in a simple novel that shaped Reagan’s character as a child growing up in Dixon, Illinois.

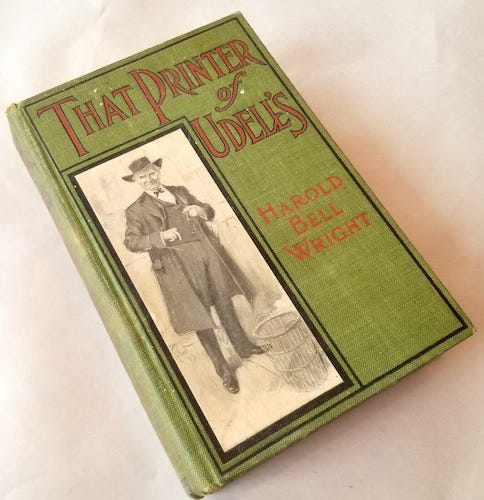

During their meeting, the former Soviet agent walks to his bookshelf and pulls out an obscure book: That Printer of Udell’s by Harold Bell Wright. He recounts how Reagan’s mother Nelle, a devout Christian, gave the novel to 11-year-old Ronald. After reading the book, Reagan asked to be baptized — the start of a deep faith that would grow throughout his life and ultimately drive his spiritual battle against communism.

A Tale of Practical Christianity

The book’s main character (Dick Falkner) had a drunken father and a nomadic childhood, circumstances that no doubt resonated with a young Reagan amid similar hardships.

Above all, Falkner and young business owner George Udell were excellent role models embodying the book’s central theme of practical Christianity — having a plan and taking action to execute God’s will.

Practical Christianity is beyond straight preaching, your church denomination, or being seen in the pews on Sundays. It’s about giving someone a chance to earn their way, as George Udell demonstrates in an early scene.

One night late at his print shop, Udell finds himself overloaded and in need of help. Off the cold street walks a desperate, disheveled Falkner. He was still searching for work after being rejected by every other place in town, including a church.

George immediately sits Dick down at a desk to see what he can do. Falkner doesn’t hesitate, doesn’t quibble over how much he’s going to get paid. No, young Dick digs in and proves himself with good work, and a partnership is born.

As Dick establishes himself at Udell’s and improves himself and his situation, his circle of influence grows within the town and church. This progression leads to Falkner devising a social welfare plan for the poor, drawing from his experience as a vagabond.

The Test of Work

At the heart of Falkner’s welfare plan lay a simple test: the willingness to work.

When someone challenges Falkner that charity breeds laziness, he responds with the following argument:

“Not if it were done according to God’s law,” answered Dick. “The present spasmodic, haphazard sentimental way of giving does [encourage laziness]. It takes away a man’s self-respect; it encourages him to be shiftless and idle; or it fails to reach the worthy sufferers.”

“But what is God’s law?” asked the other.

“That those who do not work should not eat,” replied Dick; “and that applies on the avenue as well as in the mines... Different localities would require different plans, but the purpose must always be the same. To make it possible for those in want to receive aid without compromising their self-respect, or making beggars of them, and to make it just as impossible for any unworthy person to get along without work.”

The novel’s theme of dignity through work reaches its pinnacle in the story of a young woman who chooses meaningful labor over social status.

Choosing the Better Life

Udell’s reveals work’s deeper meaning through Amy Goodrich, a wealthy young woman pushed toward an advantageous marriage to maintain social status. When her parents forbade her from teaching underprivileged children, she responded by leaving home. After finding her way to a farm, Amy discovered purpose in honest labor, tending to daily chores alongside the family who took her in.

When her parents demand she return home, Amy is resolute in her reply:

Amy looked at her [mother] steadily. “You know that a woman degrades herself when she does nothing useful, and that I count my present place and work, far above my old life at home.”

A century later, Amy’s stand for meaningful work feels prophetic. Today, her words would fall on deaf ears in a culture that prizes comfort over calling.

Work in the Post-Covid World

Reading Udell’s caused me to examine our post-covid relationship with work, particularly in white-collar industries.

Five years later, the debate over remote work versus in-office masks a deeper crisis: a fundamental shift in people’s attitude toward their job.

Beyond the desire to work from home, I’ve witnessed a growing resistance to meaningful effort. Work has become purely transactional — no longer about contribution or purpose, but about minimal engagement for maximum comfort.

The new standard? Do just enough to fund the modern luxuries: smartphones, streaming services, DoorDash deliveries, and Instagram vacations.

The dignity of work has been replaced by a culture of convenience.

Their Clear Priority

At our recent all-staff meeting, employees submitted forty questions for our owner to address. Only one asked about taking on more responsibility. None focused on improving our products or serving customers better.

The remaining questions revealed a full-court press on reducing work hours:

Can we get more clarity on our remote work policy? (We’re very clear about wanting people in the office; they don’t like our answer)

What is the protocol for snow/cold/bad weather days?

Can we get “Summer Fridays?” (They want to leave work at noon every Friday from June to September)

Can we completely close down during the last week of the year? (No, we support customer websites 24/7/365)

This mindset isn’t unique to our company. Through networking groups, we’ve learned that business owners everywhere face this same resistance to meaningful work. What began as isolated requests for flexibility has evolved into a broader cultural shift away from the very meaning of work itself.

Reclaiming Work’s Noble Purpose

The covid era ushered in more than health protocols and remote work policies. It accelerated a profound shift in our relationship with work, eroding the very ethic Reagan championed against communism. Under the banner of workplace flexibility and personal freedom, we witness the steady decay of initiative, responsibility, and pride in meaningful contribution.

Yet hope remains in daily acts of resistance. When we choose excellence over convenience and service over comfort, we echo Dick Falkner’s conviction that work builds character. Through mentoring young employees to value contribution above compensation, through persevering to serve our customers, we preserve what Reagan discovered in That Printer of Udell’s: meaningful work transforms a job from a paycheck into a calling.

To reclaim work’s nobility, we must see it as George Udell did — as a chance to lift others while building something eternal. When we give our best to meaningful labor, we not only build stronger communities — we build stronger souls.

Links:

Cinderella Man (2005) (terrific movie about the same topic)

Image credit: Alamy

Sharing Midwestern values through the stories of a hard-working single dad, all for the glory of God.